Platforms don't exist

This week’s newsletter is a little unusual. It only has one section, which is devoted to sketching out some possible contours of a left tech policy. In what follows, I take the basic principles of decommodification and democratization and try to come up with a model for how to apply them to our actually existing digital sphere.

Read on! Or subscribe.

What to do about the internet

What should we do about Google, Facebook, and Amazon? People from across the political spectrum are urgently trying to answer this question. So far, however, relatively few answers have come from the socialist left. At least in the United States, the cutting edge of the platform regulation conversation is dominated by the liberal antitrust community, perhaps best represented by the Open Markets Institute. They have some good ideas, and they’re serious about confronting corporate power. But they come from the Brandeisian reform tradition. Their horizon is a less consolidated capitalism: more competitive markets, more smaller firms, more widely dispersed property ownership.

For those of us with our eye on a different horizon, one beyond capitalism, this approach isn’t particularly satisfying. There are elements of the antitrust toolkit that can be very constructively applied to the task of reducing the power of Big Tech and restoring a degree of democratic control over our digital infrastructures. But the antitrusters want to make markets work better. By contrast, a left tech policy should aim to make markets mediate less of our lives—to make them less central to our survival and flourishing.

This is typically referred to as decommodification, and it’s closely related to another core principle, democratization. Capitalism is driven by continuous accumulation, and continuous accumulation requires the commodification of as many things and activities as possible. Decommodification tries to roll this process back, by taking certain things and activities off the market. This lets us do two things:

The first is to give everybody the resources (material and otherwise) that they need to survive and to flourish—as a matter of right, not as a commodity. People get what they need, not just what they can afford.

The second is to give everybody the power to participate in the decisions that most affect them. When we remove certain spheres of life from the market, we can come up with different ways to determine how the resources associated with them are allocated. In particular, we can come up with ways to make such choices collectively, by turning spaces formerly ruled by the market into forums of political contestation and democratic debate. If maximizing profit and maintaining class power were no longer the main considerations in the organization of our material world, what new sorts of arrangements could a democratic process generate?

These principles offer a useful starting point for thinking about a left tech policy. Still, they’re pretty abstract. What might they look like in practice?

Step One: Grab the low-hanging fruit

First, the easy part.

A portion of the internet is devoted to shuttling packets of data from one place to another. It consists of a lot of physical stuff: fiber optic cables, switches, routers, internet exchange points (IXPs), and so on. It also consists of firms large and small (mostly large) who manage all this stuff, from the broadband providers that sell you your home internet service to the “backbone” providers who handle the internet’s deeper plumbing.

This entire system is a good candidate for public ownership. Depending on the circumstance, it might make sense to have a different kind of public entity own different pieces of the system: municipally owned broadband in coordination with a nationally owned backbone, for instance.

But the “pipes” of the internet should be fairly straightforward to run as a publicly owned utility, since the basic mechanics aren’t all that different from gas or water. This was one of the points I made in a recent piece for Tribune about the Labour Party’s newly announced plan to roll out a publicly owned network and offer free broadband to everybody in the UK. It’s good politics and, even better, it works. Publicly owned networks can provide better service at lower cost. They can also prioritize social imperatives, like improving service for underconnected poor and rural communities. For a deep-dive into one of the more successful experiments in municipal broadband in the US, I highly recommend Evan Malmgren’s piece “The New Sewer Socialists” from Logic.

Step Two: Taxonomize the fruit higher up the tree

Further up the stack are the so-called “platforms.” This is where most of the power is, and where most of the public discussion is centered. It’s also where we run into the most difficulty when thinking about how to decommodify and democratize.

Part of the problem is the name: “platform.” None of our metaphors are perfect, but I think it might be time to give this one up. It’s not only self-serving—it enables a service like Facebook to project a misleading impression of openness and neutrality, as Tarleton Gillespie argues—it’s imprecise. There is no meaningful single thing called a platform. We can’t figure out what to do about the platforms because “platforms” don’t exist.

Before we can begin to put together a left tech policy, then, we need to come up with a better taxonomy for the things we’re trying to decommodify and democratize. We might start by analyzing some of the services that are currently called platforms and trying to discern the principal features that distinguish them from one another:

The first is size. How many users does the service have? Sometimes this is an easy question to answer. Sometimes it’s not, because the way we define “user” will vary, and these differences may be substantial:

Sometimes what it means to be a user isn’t all that complicated. The number of monthly active users (MAU) of Facebook, the Google product suite, and Amazon Web Services (AWS) are easy to calculate.

But what about a service like Uber or Instacart, where you have both workers (“drivers,” “shoppers”) and customers? Both are users, but they’re using different parts of the service. So it probably makes sense to include both in the overall user count.

What about a service that has “targets” that aren’t exactly users? In last week’s newsletter, I talked about the Axon policing platform that enables law enforcement agencies to connect various devices and services—bodycams, tasers, in-car cameras, a digital evidence management system, smartphone apps, etc—into a single integrated portal. The users of this platform are police officers. The targets are the individuals whose information is being recorded and processed by the platform. Should they be included in the overall user account, even though they aren’t really users? If our goal is to measure the overall impact of the service, then the answer is yes.

The second dividing line is function. What does the service do? Nick Srnicek, in his invaluable book Platform Capitalism, uses this approach to define five different kinds of “platforms,” though I’m inclined to use the word “services”:

Advertising services like Google and Facebook that hoover up personal data and monetize it by selling targeted ads.

Cloud services like AWS and Salesforce that sell various cloud-based “as-a-service” products to enterprise clients, from infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) to platform-as-a-service (PaaS) to customer relationship management (CRM).

Industrial services like Predix designed to support “industrial internet” applications like wiring up a factory with Internet of Things (IoT) devices and using the data that flows from them to optimize efficiency.

Product services like Rolls Royce and Spotify that “transform a traditional good into a service.” Rolls Royce is now renting jet engines to airlines, so that they pay by the hour instead of buying the whole thing up front, and using sensors and analytics to optimize maintenance. Spotify is turning albums into streams. The business model is subscription fees.

Lean services like Uber and Airbnb that match buyers and sellers while minimizing their own asset ownership. Matching isn’t all they do, however: gig-work services like Uber are also very much in the business of algorithmically managing and disciplining their drivers.

One could think of more types of platforms. And I might quibble with some of Srnicek’s category choices—do Uber and Airbnb really belong in the same bucket? But if we’re looking to differentiate services by function, this list is a good place to start.

The third way to split up services is by the kind of power they exercise. K. Sabeel Rahman wrote an interesting piece for Logic called “The New Octopus” that identifies three kinds of technological power:

Transmission power, which is “the ability of a firm to control the flow of data or goods.” He gives the example of Amazon’s massive shipping and logistics infrastructure controlling the “conduits for commerce,” as well as internet service providers (ISPs) controlling the “channels of data transmission.” We might also add AWS and other major cloud providers. A service like AWS S3 is essential to the flow of data across the modern internet.

Gatekeeping power, where the firm “controls the gateway to an otherwise decentralized and diffuse landscape.” He gives the example of Facebook’s News Feed or Google Search, which mediate access to online content. Here the power is held at the “point of entry” rather than across the entire infrastructure of transmission.

Scoring power, which is “exercised by ratings systems, indices, and ranking databases.” This includes automated systems for screening job applicants, for instance, or for informing sentencing and bail decisions.

Step Three: Enter n-dimensional space

We could spend a lot more time tweaking our taxonomy. But let’s leave it there, and return to the question of how we might decommodify and democratize our digital infrastructures. Given the wide range of services we’re talking about, it follows that the methods we use to decommodify and democratize them will also vary. The purpose of developing a reasonably accurate taxonomy is to help inform which methods we might use for each kind of service.

This is the logic behind Jason Prado’s argument in the latest edition of his Venture Commune newsletter, “Taxonomizing platforms to scale regulation.” Prado argues that we should be differentiating services by the number of users they have, and then implementing different regulations at different sizes. At 0-5 million users, for instance, a service should “only be subject to basic privacy regulations.” At 20-50 million, they should be required to publish “transparency reports about what data is collected and exactly how it is used.” At 100+ million, a service becomes “indistinguishable from the state” and therefore needs to be democratically governed, perhaps by a “governing board made up of owners, elected officials, platform developers/workers, and users.”

I like this basic approach, but I would expand it. Size is an important consideration, but not the only one. The service’s function and the kind of power it exercises are also significant factors.

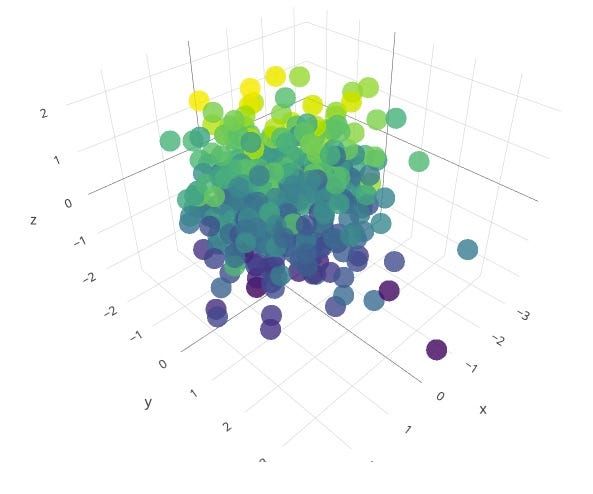

We could certainly identify more factors. But for now let’s assume size, function, and kind of power are the three most salient features of a service. We could map each feature to an axis—x, y, and z—and then plot each service as a point somewhere along those three axes. Then, depending on where the service sits in our three-dimensional space (or n-dimensional, if we refine our taxonomy by increasing our number of features), we could select a method of decommodification and democratization that is particularly well suited to the service.

What are some of those possible methods? Here are four:

Public ownership: In this case, a state entity takes responsibility for operating a service.

These entities can be structured in all sorts of ways, and exist at different levels, from the municipal to the national. Services that exercise transmission power (Rahman) or those that involve the cloud (Srnicek) are especially good candidates for such an approach. Along these lines, Jimi Cullen wrote an interesting proposal for a publicly owned cloud provider last year called “We need a state-owned platform for the modern internet.” Public ownership is also probably best suited for services of a certain scale. At the largest size, however, governance can no longer be achieved at the level of the nation-state—at which point we need to think about transnational forms of public ownership.

Public entities can also be in the business of managing assets rather than operating a service. For example, they might take the form of “data trusts” or “data commons,” holding a particular pool of data and enforcing certain terms of access when other entities want to process that data: mandating privacy rules, say, or charging a fee. Rosie Collington has written an interesting report about how such an arrangement might work for data already held by the public sector called “Digital Public Assets: Rethinking value, access and control of public sector data in the platform age.”

Cooperative ownership. This involves running services on a cooperative basis, owned and operated by some combination of workers and users.

The platform cooperativism community has been conducting experiments in this vein for years, with some interesting results.

What Srnicek calls “lean” services would lend themselves to cooperativization. A worker-owned Uber would be very feasible, for example. And there’s all sorts of policy instruments that governments could use to encourage the formation of such cooperatives: grants, loans, public contracts, preferential tax treatment, municipal regulatory codes that only permit ride-sharing by worker-owned firms. It’s possible that cooperatives work best at a smaller scale, however—you might want a bunch of city-specific Ubers rather than a national Uber—in which case the antitrust toolkit might come in handy, since we would need to break up a big firm before cooperativizing its constituent parts.

We could also think of data trusts or data commons as being cooperatively owned rather than publicly owned. This is what Evan Malmgren recommends in his piece “Socialized Media”: a cooperatively owned data trust that issues voting shares to its members, who in turn elect a leadership that is empowered to negotiate over the terms of data use with other entities.

Non-ownership. In some cases, services don’t have to be owned at all. Rather, their functions can be performed by free and open-source software.

There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of open source as an ideology—Wendy Liu’s “Freedom Isn’t Free” is essential reading on this front—but free software does have decommodifying potential, even if that potential is suppressed at present by its near-complete capture by corporate interests.

This is another realm in which the antitrust toolkit could be helpful. In 1949, the Justice Department filed an antitrust suit against AT&T. As part of the settlement seven years later, the firm was forced to open up its patent vault and license its patents to “all interested parties.” We could imagine doing something similar with tech giants, making them open-source their code so people can develop free alternatives to their services. Prado suggests that a service’s code repositories should be forced open within six months of hitting 50-100 million users.

In addition to bigger services, I’d also argue that services whose business model is advertising (Srnicek) and those that exercise gatekeeping power (Rahman) would make good candidates for open-sourcing. One could imagine free and open-source alternatives to Google Search, for instance, or existing social media services.

Another useful idea drawn from the antitrust toolkit that could help promote open-sourcing is enforced interoperability. Matt Stoller and Barry Lynn from the Open Markets Institute have called for the FTC to make Facebook adopt “open and transparent standards.” This would make it possible for open-source alternatives to work interoperably with Facebook. It doesn’t get our data off of Facebook’s servers, but it starts to erode the company’s power by giving people various (ad-free) clients that can access that data and present it differently. If these interfaces caught on, Facebook would no longer be able to sell ads and its business would eventually collapse. At which point it could be refashioned into a publicly owned or cooperatively owned data trust that furnishes data to a variety of open-source social media services, themselves perhaps federated on the model of Mastodon.

Abolition. Certain services shouldn’t be decommodified and democratized, but abolished altogether.

Governments deploy a range of automated systems for the purposes of social control. These include carceral technologies like predictive policing algorithms that intensify policing of working-class communities of color. (This is also an example of what Rahman calls scoring power.) Scholars like Ruha Benjamin and community organizations like the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition are applying the abolitionist framework to these kinds of technologies, calling for their outright elimination: in her new book Race After Technology, Benjamin talks about the need to develop “abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code.”

Another set of systems worthy of the abolitionist treatment are the forms of algorithmic austerity documented by Virginia Eubanks in her book Automating Inequality. In the United States and around the world, public officials are using software to shrink the welfare state. This deprives people of dignity and self-determination in a way that’s fundamentally incompatible with democratic values.

Another technology I would put in this category is facial recognition, which can be deployed by public or private entities. The growing movement to ban facial recognition, a demand advanced by a range of organizations and now embraced by Bernie Sanders, is a good example of abolition in action.

There is also an ecological case to be made for abolishing certain services, given the carbon-intensive nature of machine learning, the cloud, and mass digitization. This is a point I made in a recent Guardian piece.

One final note worth mentioning: while the goal of a left tech policy should be to strike at the root of private power by transforming how our digital infrastructures are owned, we will also need legislative and administrative rule-making to govern how those infrastructures are allowed to operate. This might take the form of GDPR-style restrictions on data collection and processing, measures aimed at reducing right-wing radicalization, or various algorithmic accountability mandates. These rules should apply across the board, no matter how the entity is owned and organized.

The above is a provisional sketch. It has lots of holes and rough edges. Plotting all the major services along three axes according to their features may ultimately be impossible—and even if it can be done, it runs the risk of locking us into an excessively rigid model for making policy. More broadly, there are severe limits to this sort of programmatic thinking, which can too easily tilt in a technocratic direction.

Still, I hope these thoughts offer some preliminary materials towards developing a left tech policy that takes the basic principles of decommodification and democratization and tries to apply them to our actually existing digital sphere. At the moment there is relatively little political space for such an agenda in the United States, but there may come a time when more space is available. It would be good to be ready.