The dead are at our backs

Welcome to this week’s edition of Metal Machine Music.

Here’s what I’ve got for you:

Why the tech left needs a usable past

How a bunch of British socialists tried to make technology more democratic back in the 1980s, and what lessons their experiments might hold for today

A roundup of things to read, mostly related to labor (no surprise there)

Subscribe to get this newsletter in your inbox, or read on.

A usable past

I’ve included some history in each of these newsletters so far. This is partly because I love history and find it endlessly fascinating. But it’s also because history has real political value. The tech left needs a usable past.

We’re not the first generation that has attempted to construct a more democratic relationship to technology. On the contrary: we belong to a long tradition of movements and organizations that have done this work in the past. This includes people like Joan Greenbaum, who (among other things) organized tech workers in the 1960s and 1970s with a group called Computer People for Peace. (If you haven’t read it already, I highly recommend the interview we did with Joan in Logic, “Mainframe, Interrupted.”)

People like Joan are not typically featured in the stories we tell about tech. They deserve to be more widely known.

But for the tech left, people like Joan also serve a more specific function. They’re our elders, our ancestors. We can draw ideas and inspiration from them. They can also help us feel a sense of belonging. They can help us feel anchored to a community that exists not merely across space but also across time, a community of the living and the dead.

It might sound strange, but I take great comfort in the idea of being surrounded by ghosts. In his beautiful and heartbreaking Memoirs of a Revolutionary, Victor Serge reflects on having outlived so many of his comrades, most of whom had been massacred in one counterrevolution or another:

I must confess that the feeling of having so many dead men at my back, many of them my betters in energy, talent, and historical character, has often overwhelmed me, and that this feeling has been for me the source of a certain courage, if that is the right word for it.

This summer, I visited the cemetery in Berlin where Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht are buried. In the center is a large stone with the following words engraved on its surface: “Die Toten mahnen uns.” The dead admonish us, the dead remind us; the dead are at our backs, urging us forward.

Innovation from below

Now for some actual history.

The year is 1981. The left wing of the Labour Party has just won control of the Greater London Council (GLC), a municipal body that governs London alongside various borough-level councils.

The story of the GLC is well worth revisiting today, particularly for those interested in municipal socialism and/or the intellectual genealogy of Corbynism. (Corbyn’s shadow chancellor John McDonnell got his start as the finance chair and deputy leader of the GLC.) But for our purposes, what’s most relevant is the fact that the GLC undertook some very interesting experiments around democratizing technology.

A core component of the GLC’s economic program was the Greater London Enterprise Board (GLEB). At the time, London had fairly high unemployment, in large part due to deindustrialization. The purpose of the GLEB was to promote economic development while also promoting economic democracy. This involved doing things like putting public money into firms that offered good, unionized jobs, as well as encouraging the creation of worker-owned cooperatives.

It also involved establishing five “Technology Networks” in different locations across London. (In what follows, I’m indebted to Adrian Smith’s invaluable article on the subject, “Technology Networks for Socially Useful Production.”)

These Technology Networks were prototyping workshops—a bit like hackerspaces today. People could walk in, get access to machine tools, receive training and technical assistance, and build things. The things they built went into a shared “product bank” that other people could draw from, and which were licensed to companies to help finance the Networks. The innovations that emerged included wind turbines, disability devices, children’s toys, and electric bikes. Energy efficiency was an area of special emphasis.

For some of the folks involved in the effort, the goal was to stimulate local business development. Others, however, saw the Technology Networks in a more radical light. The purpose of these spaces, they believed, was to democratize the design and development of technology.

This meant creating a participatory process whereby working-class communities could obtain the tools and the expertise they needed to make their own technologies. It meant producing to satisfy human need—what organizers at the time called “socially useful production”—rather than to maximize profit. In his article, Smith quotes from Mary Moore, a participant in one of the Technology Networks (bolding mine):

...making sure that what you do is going to be of real use to the intended users […] means somehow getting them to take part in the design process rather than just pop in with a product when you’ve produced it ... So you wouldn’t just market-research a new product, which puts users in a passive role. You’d actually get them in the workshop and enable them to learn more about how such things are made and designed and repaired and modified

Innovation from below, in other words.

The more radical members of the Technology Networks also saw them as sites of political mobilization. The act of prototyping products in a workshop could serve as a useful starting point for a broader conversation about what kinds of transformations would be needed to create a more equitable society. In the process of trying to solve their problems with technology, people came to realize that technology often fell far short of solving their problems. Politics was also needed. Along these lines, one of the Networks kick-started a political campaign called “Right to Warmth” that involved organizing community energy efficiency initiatives, creating local energy cooperatives, and pressuring Thatcher’s government into putting more money towards energy conservation measures.

Sadly, the Technology Networks were relatively short-lived. Thatcher abolished the GLC in 1986, and the Networks eventually disappeared.

So what are some possible takeaways for today?

In recent years, a number of socialists have won local elections in the US. (Including some this week.) It’s conceivable that they could push municipalities to create something like Technology Networks. In some ways, running such spaces might be easier today. You don’t need machine tools to prototype software; you can do everything with open-source tools on cheap hardware. We’ve also got 3D printers now, if stuff you can touch is your thing.

Still, plenty of problems remain. The original Technology Networks were riven with tensions between people who saw them as engines of business development and people who saw them as engines of social transformation. It’s easy to imagine the same tensions emerging in similar spaces today. It speaks to the contradictions that attend any socialist governing experiment within advanced capitalist societies, even (or perhaps especially) at the municipal scale: how does one steer (or at the least not blow up) the economy while simultaneously trying to completely restructure it?

In the US today, we have a few different kinds of spaces that resemble Technology Networks in one way or another: the hackerspace, the startup incubator, and the foundation-funded NGO. But I doubt that any of these spaces are capable of serving as catalysts for meaningful social change. Hackerspaces are about helping people do fun creative projects; startup incubators are about helping people launch businesses; foundation-funded NGOs are about helping people find less disruptive channels for their discontent. I think we need alternatives. Technology Networks, at least in their more radical aspects, might offer a way to think about what those alternatives could look like. For me, the question worth asking is: How do we create spaces of democratic technological practice that politicize participants and develop their capacity for self-organization?

Finally, a few more readings in this vein:

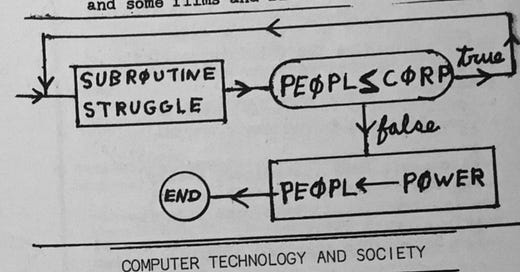

The GLEB published a promotional booklet about the Technology Networks in 1984 that’s a real gem. The picture above is drawn from the booklet. Thanks to Adrian Smith for digitizing.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of the GLC, take a look at Michael Rustin’s “Lessons of the London Industrial Strategy” from the New Left Review. (I canvassed some British friends on Twitter and this came up—thanks to Will Davies for the recommendation.)

The GLEB’s technology director who created the Technology Networks was Mike Cooley, one of the leading figures behind the Lucas Plan. The Lucas Plan was a 1976 document produced by the workers of an aerospace company proposing a democratic reorganization of the firm around socially useful production. If you’d like to learn more about the Lucas Plan, check out Adrian Smith’s article in the Guardian and this 1978 documentary on YouTube.

Other readings

Time to wrap up. In conclusion, here’s a brief rundown of a few other things I’ve been reading:

Brian Dolber has produced an interesting report for the MIC Center called "From Independent Contractors to an Independent Union.” It looks at how the LA-based organization Rideshare Drivers United (RDU) has used social media ad buys and its own in-house smartphone app to organize drivers. Groups like RDU are finding creative ways to overcome the challenges of organizing atomized, algorithmically managed app workers—which includes making their own apps.

Speaking of app workers, several thousand Instacart workers recently concluded a 72-hour strike. Read their open letter to the company’s founder, which outlines their grievances and demands. As April Glaser explains in “Instacart Workers Are Striking Because of the App’s User Interface” over at Slate, the dispute partly revolves around the Instacart app’s default tip setting: it’s currently set at 5 percent, and workers want it set at at least 10 percent. Design is a terrain of class struggle!

It was recently the one-year anniversary of the Google Walkout, a watershed moment in the story of the tech worker movement. Read the Medium post written by Googlers to commemorate the occasion, and their Year in Review in tweet form. It’s been a long year, and it’s not over yet.