The technologies of all dead generations

A couple days ago, I keynoted a conference at Penn’s Annenberg School organized by David Elliot Berman, Victor Pickard, and Briar Smith. It was called “Democratizing the Internet: Platforms, Pipes, Possibilities,” and it brought together a wonderful collection of people, who shared their work on the political economy of the internet and offered their thoughts on what should be done to improve things.

Since publishing my book last year, I’ve been trying to find a new way into these topics. I still agree with everything I wrote in the book, and will happily recite talking points from it when called upon. But I don’t find the framing especially exciting anymore. To keep writing about the internet, or even technology in general, I’ve felt the need to find new lines of approach.

My talk at Penn represents one attempt at doing so. More specifically, it’s a meditation on a question that has been bothering me recently: How do we get from our degraded technological present to a better technological future? The text of my talk, “The Technologies of All Dead Generations,” is included below.

Note: Your email provider, like Gmail, will probably truncate this message for being too long. If you don’t want your reading flow to be interrupted, you can read this post on the web by clicking the title (“The technologies of all dead generations”) above.

I’d like to talk to you today about the possibilities for creating a better technological future. But before I do, I’m going to tell you about a near-death experience I had in an airplane.

Somewhere in the Atlantic are the Azores, and somewhere in the Azores is Lajes Airport. It sits on an island shaped like an almond, made from the merger of four volcanos. The Portuguese settled the place in the 15th century. In the 20th, it became a popular pit stop for US military aircraft transiting the Atlantic.

Late last year, I landed there on a malfunctioning Airbus A321. We were flying from Lisbon to Boston. At some point, the pilot discovered the fuel tanks were broken. If we didn’t land soon, he said, we would run out of gas. He pointed the plane downwards and began a rapid descent. The ocean looked cold. I wondered if I would pray, if I would have time to pray, what the words of my prayer would be.

Then the woman sitting in the row behind me said that if we crashed in the Atlantic, among the things that would be lost, aside from two hundred lives, would be her Bitcoin holdings. This is because her backpack contained what’s known as a “hard wallet,” a storage device that holds the cryptographic keys that confer ownership of a particular quantity of digital currency. And this remark—made jokingly, I think, as an attempt to defuse the tension that was accumulating in the minds of the passengers, as we each privately reflected on the prospect of swallowing salt water in the dark—initiated a conversation between her and the older man seated next to her, a conversation that continued long after we had jolted to a landing at Lajes Airport and the technicians had emerged from the surrounding buildings to begin fixing the plane.

He wanted to know how Bitcoin worked; she explained. Some amount of semi-technical language was used; the conversation came to a halt. A moment passed. Then he replied that he was reading a book about how every civilization throughout history that went to shit did so because they had devalued their currency. The case in point was Nero. That pervert had reduced the precious metal content of Roman coins in order to fund increased government spending, which in turn facilitated all sorts of bad behavior—loose money, loose morals—and thus fatally weakened the empire. The lesson was that monetary debasement always prefigures and produces a moral abasement that eventually leads to total social collapse.

I thought this was a non sequitur, the kind of thing that certain men say because they’re not really paying attention. And the politics of it, the implicit critique of Biden, seemed like it would rankle, because, by diction and dress, the man was coded as conservative while the woman was coded as liberal.

I was wrong. The woman agreed, vigorously. And the conversation, which had so far advanced by fits and starts, found a deeper channel. They were friends now. See, Bitcoin was pervert-proof: no Nero could abase it because the total number of coins was capped at 21 million, thus rendering inflation impossible—not actually, I wanted to interject—and its “trustless” architecture made it immune to the meddling evils of central banking and the regulatory state—again, not actually. Before long we were back in the air, fuel tanks fixed. I put on my headphones to watch a movie.

I knew nothing about this woman. But it was evident that her experience with Bitcoin had helped imbue her with a particular politics, a politics somewhat bloodlessly known as libertarianism but which could more descriptively defined as a melange of paranoia and misanthropy, seasoned with various exotic and incorrect ideas about how the economy works. This politics, as the scholar David Golumbia has argued, is embedded into Bitcoin as a technology. It serves as the basic conceptual substrate upon which the software is built. “Bitcoin activates or executes right-wing extremism,” Golumbia writes, “putting into practice what had until recently been theory.”

It would be reasonable to regard this phenomenon with alarm. At a time when right-wing politics is distressingly popular around the world, Bitcoin offers yet another boost to the forces of reaction. But what I remember feeling on the airplane was envy. Why can’t we do that, I wondered. If there are technologies that propagate selfishness, why can’t we make technologies that propagate solidarity?

***

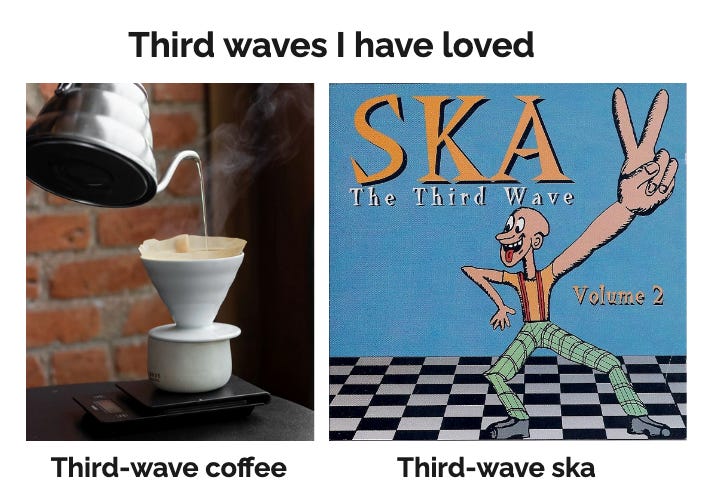

The law professor Frank Pasquale says there have been two waves of research and activism around “algorithmic accountability.” The first wave was about “improving existing systems,” while the second wave was about asking whether certain systems “should be used at all—and, if so, who gets to govern them.” One of his examples is facial recognition software. A first-waver would point out that such software typically does a bad job with faces that aren’t white. A second-waver would ask, “if these systems are often used for oppression or social stratification, should inclusion really be the goal?” Why not abolish them, or at least severely restrict their use?

As distinct as these two waves are, they share something in common. Both arrive after the fact, to critique an existing technology. There is a further step that needs to be taken, however. At some point, we need to move from critique to creation. And this move just might serve as the basis for a third wave of algorithmic accountability, which would concern itself not with ameliorating or abolishing existing systems, but with building new ones.

Importantly, the different waves don’t displace each other but, like real waves, interpenetrate. Harm reduction is an important complement to abolition; and both, in turn, can help clear the space in which alternatives may emerge. We’ve already seen evidence of this dynamic in recent years, as the first two waves of algorithmic accountability have helped stimulate greater interest in different forms of technological practice, particularly when it comes to the internet.

There are now a number of ongoing experiments with things like collectively governed social media sites and worker-owned app-based services, and increased enthusiasm for well-established alternative ownership models like publicly and cooperatively owned broadband networks.

The third wave of algorithmic accountability, then, is already in motion. It’s a welcome development, and one that I wholeheartedly support.

But I’m also wary of it. There is a sense of relief when one moves from critique to creation. It satisfies the familiar American impulse to be practical, constructive, solution-oriented. And this introduces a danger, which is that in the comfort we derive from finally doing something rather than just talking and writing and analyzing and arguing, we get too comfortable, and act without an adequate understanding of the difficulties that condition and constrain our activity. For our efforts to have any chance of success, we need that understanding. And to acquire that understanding, we need critique. We can’t move beyond it.

Critique is how we make the map of the terrain that the creativity of the third wave must traverse.

This terrain is contradictory, and thus compels us to think in contradictions, and to be patient in doing so. “Progress does not take place like a ‘shot out of a pistol,’” Grace Lee Boggs once wrote. “It requires the labor, patience, and suffering of the negative.” Boggs was a Hegelian, for whom the working through of “the contradictions or limitations inherent in any idea” is the dialectical process whereby we arrive at better, more developed ideas. Here she is counseling us not to rush the negative moment of the dialectic, to sit with the contradictions rather than hurrying to resolve them.

In that spirit, let’s embrace negativity and suffer together serenely, as we return to the question that I asked on the airplane: If there are technologies that propagate selfishness, why can’t we make technologies that propagate solidarity?

***

This is, in fact, the animating question of the third wave. Another way of asking it is: How can we do politics through technology?

First, a definition. What is politics? Let’s say that politics is the set of practices through which a group of human beings arrive at a particular distribution of social power. Let’s say, further, that capitalism is inherently depoliticizing.

Capitalism introduces what appears to be a natural separation between the political and the economic, with the latter understood to be a space of impersonal, automatic “market forces.” This is why capitalist societies, in the words of the philosopher Tony Smith, “systematically generate an impoverished form of ‘the political.’” Officially, politics is confined to the state, or really just a segment of the state.

One way to see the history of social movements under capitalism is as a series of struggles against the impoverishment of the political. The labor and socialist movements politicized the economy. The feminist, queer liberation, and Black liberation movements politicized many other zones of social life, from the family to the school, the household to the lunch counter.

We could place the three waves of algorithmic accountability within this lineage. They all represent attempts to politicize technology.

But there is an important distinction to be made between the first two waves and the third. The first two waves make technology an object of politics, but they generally target regulatory and legislative solutions—which is to say, their interventions largely remain within the realm of official politics. For example, a first-waver might demand that regulatory agencies submit automated systems to algorithmic audits or impact assessments in order to identify biases, while a second-waver might demand a legislative ban on certain types or uses of software, like facial recognition or targeted advertising.

The third wave, by contrast, not only makes technology an object of politics but a terrain of politics. It wants to do politics through technology. And this means that the third-waver must develop an analysis of the specificities of technology as a site of political struggle, in the same way that feminists had to develop an analysis of the specificities of the household as a site of political struggle. To do politics through technology, we need to understand how technologies do politics.

***

Among those who study technology for a living, it is a commonplace that artifacts have politics. This is the famous formulation of the theorist Langdon Winner, who points out that the political qualities of a technical object—which is to say, how it alters the existing distribution of social power—are, at least in part, internal to the object itself.

One of Winner’s examples is drawn from Robert A. Caro’s biography of Robert Moses. According to Caro, Moses designed the overpasses on his Long Island parkways to be too low for buses to drive under them. He did so, Caro says, in order to prevent poor people, and particularly poor Black and Puerto Rican people, from getting to Jones Beach. Thus even a fairly unsophisticated artifact like an overpass can, simply by virtue of its dimensions, embody and enact a political project.

We could arrive at the same insight through Marx. Sometimes Marxists make too much of the distinction between the “forces of production”—the tools and techniques used to make the means of life—and the “relations of production”—the set of human relationships through which the means of life are made. But, as Marx’s own work makes clear, this is a false distinction. Productive forces always materialize within a certain matrix of social relations, and act upon those relations in turn.

Take what is possibly the most consequential technology in human history: the steam engine. Its modern iteration appeared in the late eighteenth century, and conquered the British cotton industry by the middle of the nineteenth. In doing so, it displaced a competing technology: the waterwheel.

As Andreas Malm has shown, the steam engine was not necessarily more advanced than the waterwheel. It did not produce more power at lower cost. It did produce portable power, however, and this was the secret to the technology’s success.

River power could only be tapped in certain places: a waterwheel had to be built alongside a suitable stream. This presented a problem for the owners of cotton mills. The countryside was where the streams were, but it was sparsely populated. Workers had to be imported, trained, and housed in “colonies” near the mills. They were often unreliable and insubordinate, which stalled production and suppressed profits.

The steam engine, by contrast, didn’t care about geography. A steam-powered mill could be built anywhere. So capitalists began building them in cities, where, unlike the countryside, there were plenty of workers, many of whom were already used to the long hours, monotonous work, and despotic discipline of the new industrial system. They could be hired and fired as needed, without having to be housed or trained.

The greater mobility of steam thus enabled the British cotton industry to develop a cheaper and more obedient workforce. It helped create a different kind of relationship between two groups of people: those who owned the mills and those who worked in them.

The story of the steam engine illustrates an important aspect of technologies having politics. The politics of a technology is deeply involved in determining that technology’s viability. Steam power stuck because its political qualities helped advance the interests of a rising industrial capitalist class, who could use it to strengthen control over labor and increase profits. One could tell similar stories about any number of other technologies. There are always different ways to stage and to solve a technical problem, or even to define what counts as a problem. Which sets of choices win out has mostly to do with how well they satisfy the compulsions of capital accumulation, and the projects of empire and racial subordination through which those compulsions have historically been expressed.

***

Together, these winning choices, as materialized in particular artifacts, form our technological inheritance. Marx famously observed that human beings don’t make history under conditions of their own choosing but, rather, under those transmitted from the past—that “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” This is especially true when it comes to technology. An engineer or a designer is never working from a blank slate. They are always working within conditions transmitted from the past. And this introduces a problem for the third wave of algorithmic accountability.

How do you take a technological inheritance that has been engineered for empire, racial subordination, and capital accumulation, and turn it against itself? How do you pursue a politics of liberation through a medium that is permeated with a politics of domination? If the technologies of all dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living, then how do we wake up from the nightmare?

A concrete example may help bring this dilemma into sharper focus. You’ve probably heard of Mastodon. It’s a network of social media servers that runs on open-source software. It’s been around for years, but has attracted more attention since Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter. In many ways, Mastodon is the paradigmatic third-wave project. Its creator, Eugen Rochko, has been quite explicit about his desire to create a version of social media that is driven by a very different set of values.

The first core value is anti-commercialism. Mastodon has no advertising—there are no paid, promoted, or targeted ads. (Rochko’s software development work is crowdfunded and most of the Mastodon servers are volunteer-run.) Relatedly, there is no algorithmic feed that sequences content in such a way as to maximize user engagement for ad revenue. On Mastodon, the feed is reverse-chronological.

The second core value is what you might call “devolved content moderation.” The decentralized nature of Mastodon means that content moderation is devolved to the server level. In some cases, this has enabled experiments in democratic moderation, where decisions are made collectively by the users of the server. In any case, Rochko encourages Mastodon instance to moderate content more rigorously than corporate social media platforms. In fact, to be officially listed on the main Mastodon page, admins must commit to “actively moderating against racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia.” Further, particularly egregious servers can be isolated from the rest of the network through “de-federating.” This is what happened when the fascist social networking site Gab created a Mastodon instance: most of the other servers responded by blocking it.

But if you’ve used Mastodon, you also know that it looks and feels a lot like Twitter. You follow people and see their tweets—which Mastodon calls “toots”—in your feed, alongside little icons of their profile pictures. You can reply to a toot, “boost” (retweet) it, and “favorite” (like) it. There are DMs and threads, big accounts and little accounts, memes and reply guys.

Mastodon, in other words, has inherited the basic grammar of social media as configured by Twitter. And the question that we have to consider is to what extent this inheritance complicates, or perhaps even obstructs, the political program that has been (quite consciously) encoded into Mastodon as a technical artifact. Does it matter that Mastodon so closely resembles a platform whose guiding principles—maximization of user engagement in order to monetize user attention, centralized and opaque content moderation practices—are so antithetical to it? And if so, how precisely does it matter—what effects does it have?

I am not going to attempt to answer these questions. I suspect they are not answerable in the abstract anyway, but can only be taken up concretely, by trying things out and seeing what happens.

I said before that critique is how we make the map of the terrain that the creativity of the third wave must traverse. It turns out to be even more deliciously dialectical: the map is made as the terrain is traversed. Critique and creativity advance together, through experiment. Without an inkling of the contradictions that lay ahead, the third-waver is doomed. But without moving ahead, the third-waver never has the opportunity to experience those contradictions up close and thus learn what challenges they may pose for her project.

This all sounds pretty daunting. It’s not really what one says when you’re trying to get people to contribute to your open-source software project. I don’t think the situation is hopeless, however. In fact, there is a measure of hope to be found here. But we will need to switch registers for a moment to retrieve it, and shift from the social to the psychic.

***

When we are talking about the contradictions of working within and against our technological inheritance, we are talking about the relationship between the past and the present. This relationship is a central concern for psychoanalysis. An important psychoanalytic insight is that people have trouble with this relationship: in particular, they have a hard time distinguishing past and present. There is no time in the unconscious, Freud said. The clocks, in Ingmar Bergman’s memorable image, have no hands. And this bears upon our behavior in all sorts of ways. We continuously reenact childhood traumas as adults; we meet someone new and feel like we’ve known them our whole lives.

The job of the analyst is to bring this confusion to consciousness, so as to help the patient identify a boundary between past and present. This is necessarily a porous boundary—the person remains a product of their history. But by positing a break, however incomplete, with that history, one becomes a little bit freer to move beyond it. Nothing more can happen in the past. The present affords a greater range of motion.

You don’t actually have to become a carbon copy of your parents. In fact, people rarely do: the past never completely encloses the present. There is always a discontinuity of some kind. The writer Alex Colston theorizes that this discontinuity is what makes revolutions possible. “If this separation and independence did not exist between older and newer forms of society—or families and generations themselves—all social reproduction would produce mimetic and homogeneous replicas,” he writes. “This gap is conditio sine qua non for revolution and unthinkable without it.” But breakthroughs, whether of the psychic or the social sort, don’t happen automatically. It takes work to turn discontinuity into disobedience.

These concepts apply equally well to technology. Our technological inheritance is also mediated by a degree of discontinuity. Here too, the past does not completely enclose the present. On the one hand, the artifacts that populate our technological present carry a politics that has been molded by racial capitalism and its many imperial enterprises. Yet they are not comprehensively determined by those politics. This is because, as Winner writes, technology “always does more than we intend.” Technological systems are unpredictable. They tend to create “a complex set of linkages that continues beyond one’s original anticipation.”

Winner calls it “drift”: the process whereby a technology imposes requirements of its own, pulling us ass-backwards along an unchosen course.

For example, the steam engine demanded an energy-dense and easily transportable fuel in the form of coal, thus initiating the hydrocarbon dependency that would eventually rewire the entire economy, with far-ranging ecological consequences. This didn’t obviate the steam engine’s advantages to industrial capitalists in helping to secure a lower-cost labor pool, but it did impose a new and unforeseen set of obligations.

Sometimes, however, these obligations can actually override a technology’s politics. My favorite example is the invention of the first “high-level” programming languages such as COBOL in the 1950s. One motivation for creating these languages was to produce a simpler way to write code, which would in turn enable managers to deskill software development in order to reduce labor costs. It didn’t work, however: these new languages turned out to be more complex than initially thought. In subsequent years, demand for programmers actually grew.

Drift is the entropy, the quantum of chaos that haunts the politics of technology. And at first, it may look like yet another headache for the third wave of algorithmic accountability. Pity the third-waver: first she must work under the weight of a hostile technological inheritance, and now, even if she manages to inscribe an artifact with a politics of liberation, those politics may be muddled, even undermined, by drift. Doing politics through technology is hard. You have about as much control as someone piloting a hot air balloon; it’s hard to know exactly where you’re going to land.

But drift also presents the third-waver with an opportunity. Drift is the discontinuity within our technology inheritance. And, as with our psychic and social inheritances, discontinuity can serve as the basis for disobedience. We can step into the cracks and use them as points of subversion. The technological environment into which we have been born does not perfectly abide by the imperatives that have formed it, and this gives us room for redirection. Both the computer and the atom bomb were invented by capitalist countries to defeat global fascism, but a computer can be put to more purposes than warfare. It could probably even be used to plan a socialist economy.

While the past does not completely enclose the present, it is equally true that we can never escape the past. History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” says Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses. But history never ends. Earlier, I asked: If the technologies of all dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living, then how do we wake up from the nightmare? The answer is: we can’t. But we can wake up inside the nightmare.

***

Waking up inside the nightmare is called dialectics. “Dialectics is the self-consciousness of the objective context of delusion; it does not mean to have escaped from that context,” writes Adorno in Negative Dialectics. “Its objective goal is to break out of the context from within.”

For Adorno, this goal can never be completely achieved. There is no exit to that higher synthesis that Grace Lee Boggs spoke of, just the perpetual motion of dialectical cognition, restlessly picking away at the “inadequacy of thought and thing.” Think of a firefly in a jar: it buzzes around, trying to break out, and in doing so, illuminates the air around it. “It lies in the definition of negative dialectics that it will not come to rest in itself, as if it were total,” Adorno says. “This is its form of hope.”

What a pain in the ass. But pain is information. There is a medical condition called congenital insensitivity to pain that makes it impossible for a person to feel pain. It’s very dangerous. If you don’t have access to the information of pain, you can seriously injure yourself without realizing it.

So the “suffering of the negative,” as Boggs called it—the negative dialectics of waking up inside the nightmare and probing the gaps, the contradictions—is indispensable to the work of creating a better technological future. Without it, you can do great injury to your politics.

Not by failing, which is inevitable—failure is part of the experimental process through which a new technological politics will discover the practical forms that are adequate to it. I have in mind a different kind of failure, the sort that comes disguised as success. Disobedience can resurrect what it rejects; the revolution can become the counterrevolution.

As the third wave of algorithmic accountability tries to build a new world in the shell of the old, all I’m asking is that we be mindful of the shell, that we keep faith with the traditions of critique that can help clarify the conditions within which our creativity must operate, that we cultivate some dialectical combination of humility and recklessness, and that we do our best to make something new in history without holding on to any hope of escaping it.

Love the idea of a "third wave" and I think the concept of a dialectic is really helpful to stay motivated. I think what is key is to stay humble and own it when you mess up, which you inevitably will.

When I first delved into serious tech criticism, I felt so helpless that I wanted to quit being an engineer. Now I teach a course that's intentionally half seminar, half design studio, with the aim of doing exactly as you describe here. I frame design as a three step process, drawing on context (history), critique (the "studies") and rebuild (engineering). The process was inspired by a post by Sara Hendren, but I added context because I think effective critique needs to be grounded in history to be really impactful. https://sarahendren.com/2020/06/30/critique-or-repair-a-call-to-know-your-post/

Syllabus in case anyone is interested: https://maggiedelano.notion.site/ENGR-053-Fall-2022-Syllabus-d3e6bc89973348f597b4add4ca2021ea

This is great. It reminds me of the work by David Noble, “Progress without people.”