Discipline at a distance

Welcome to your next installment of Metal Machine Music. I’ve fallen a little behind on my weekly cadence—which, fair warning, will probably keep happening. But I was very pleasantly surprised by how widely my last post, “Platforms don’t exist,” traveled. Jacobin published an edited version, and I’ll be doing a couple of interviews this week on the themes of the piece. It might also serve as the basis for a bigger project.

Anyway, on to today’s newsletter. As always, if you want this in your inbox, you can subscribe.

Elastic factories

Katrina Forrester has a very interesting piece in the London Review of Books called “What counts as work?” It’s a review of a new-ish book by Colin Crouch, Will the Gig Economy Prevail?, and it has some important insights into what we call the gig economy.

One of the questions I always struggle with when thinking about digital things is the precise balance between continuity and discontinuity. What’s old and what’s new? The mainstream tech conversation tends to emphasize discontinuity—everything digital is treated as a sharp departure from the past. Clearly, this interpretation serves certain interests: if particular products and services really are unprecedented, then the firms that produce them acquire a certain prestige as innovators, and can make the case that laws and regulations that might impinge on their profits are too antiquated to apply to this brave new world.

We might be tempted to react to this narrative by drawing the exact opposite conclusion—that nothing about “tech” is novel. But this would be wrong. There are discontinuities and continuities, and they’re often deeply entangled with one another. Trying to identify which is which, and how they’re connected, is essential for thinking through what tech is and how it works.

This is the approach that Forrester takes in her review. On the one hand, she makes the point that the gig economy strongly resembles the “putting-out” system that existed in an earlier era of capitalism in the Global North, and which still exists in the Global South. Under such a system, subcontractors perform piece work. “Non-standard” employment prevails—that is, not formal, full-time work of the kind we have come to see as normal. For most of the history of capitalism, in fact, normal work was non-standard employment:

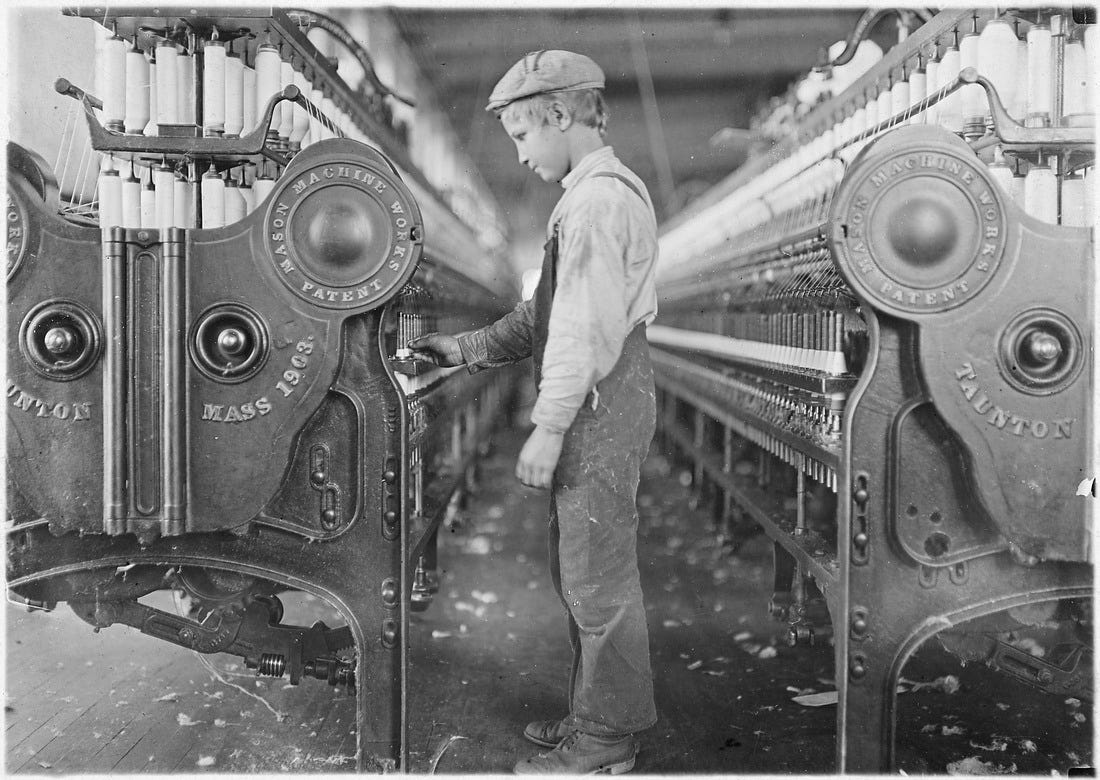

Historically speaking, standard employment has been the norm only briefly, and only in certain places. Until the ‘industrious revolution’ of the 18th century, work was piecemeal. People worked where they lived, on the farm or at home: in the ‘putting-out system’—which still exists in cloth production in parts of the global South—manufacturers delivered work to workers, mostly women, who had machinery at home and organised their work alongside their family life. Then work moved out of the home. Over the next two centuries, the workforce was consolidated into factories, then into offices. Waged work was standardised, then became salaried.

Reading this, I’m reminded of a passage from Michael Denning’s “Wageless Life”:

Unemployment precedes employment, and the informal economy precedes the formal, both historically and conceptually. We must insist that ‘proletarian’ is not a synonym for ‘wage labourer’ but for dispossession, expropriation and radical dependence on the market. You don’t need a job to be a proletarian: wageless life, not wage labour, is the starting point in understanding the free market.

Clearly there’s a continuity here: what we now call “gig work” is a permanent feature of capitalist economies. That doesn’t mean it always looks the same, however. “Modern precarity takes a distinctive form,” Forrester writes, “which is a result of the major political and economic changes of the 1970s.” These changes are known by a few different names—neoliberalism, post-Fordism, deindustrialization—but their consequence is the erosion of standard employment, particularly its “enriched” social-democratic variant, which secured a range of rights and benefits for a significant portion of the workforce in the Global North.

Where does “tech” fit into all of this? One argument often heard on the left is that tech companies owe their fortunes mostly to legal and political maneuvering rather than to technological innovation. Uber seems like a case in point. Their business model rests on the fiction that drivers are independent contractors, a fiction that they help sustain with lots of lobbying dollars. But the technology also matters. Depending on the firm, it may not be the single most determinant factor in how they make money. But it does have a specific effectivity of its own.

This specific effectivity is at the heart of how the gig economy relates to the putting-out system. One of the problems with the putting-out system is that the capitalist who pays the various subcontractors doesn’t have much control over the labor process. If people are doing piece work at home, they are generally working at their own pace, on their own terms, with their own tools. Capitalists can’t transform the labor process because they don’t control it. The rise of the modern factory system is in large part a response to this problem: manufacturers begin to put workers under the same roof in order to more closely control their work. This greater control in turn enables a (very) full working day, speed-ups, mechanization, a complex division of labor—all of which greatly enhance profitability.

Yet this new model also creates problems of its own. Concentrated in factories, workers are now potentially a lot more powerful. They can disrupt production far more easily and at a far greater scale than they could as relatively isolated subcontractors in a putting-out system. Thus the extraordinary militancy of the industrial worker, which, as Beverly Silver explores in her book Forces of Labor, crops up wherever mass production appears.

But what if you could have the advantages of both systems? What if you could control the labor process and keep workers as relatively isolated subcontractors? This is precisely what networked digital technologies make possible. As Forrester writes:

What is new about the gig economy isn’t that it gives workers flexibility and independence, but that it gives employers something they have otherwise found difficult to attain: workers who are not, technically, their employees but who are nonetheless subject to their discipline and subordinate to their authority.

Creating a hybrid of the factory and the putting-out system is feasible because networked digital technologies enable employers to project their authority farther than before. They enable discipline at a distance. The elastic factory, we could call it: the labor regime of Manchester, stretched out by fiber optic cable until it covers the whole world.

It’s important to note that this isn’t a recent phenomenon. It’s been going on ever since computers, and more specifically computer networking, began entering the corporate world. Joan Greenbaum, in her book Windows on the Workplace, talks about how even before the internet, computer networking let companies relocate “back-office” functions offsite and, eventually, offshore. Mainstream commentators are likely to put the emphasis on communication when describing this phenomenon. The very terms that are used to describe these developments—telecommunications, information and communications technology (ICT)—reflect that emphasis. But as good cyberneticians, we know that communication is also always about control. And when we situate the rise of networked digital technologies within the broader history of capitalism, it becomes clear that control—specifically, control of the labor process—is where our emphasis should be.

That said, there are novel elements to how the current crop of networked digital technologies are implementing discipline at a distance. (See what I mean about how entangled the continuities and the discontinuities are?) The sophisticated forms of algorithmic management deployed by a company like Uber through their driver app wouldn’t be possible without various advances in machine learning and the development and proliferation of the smartphone, for instance.

How does one organize in the elastic factory? Uber and Lyft drivers are figuring it out, partly by building their own apps. It’s fair to say that such workers have less structural power at the point of production than, say, autoworkers in the 1940s. But they certainly still have some power, and they’re currently innovating the organizational forms that will help them exercise it.

Municipal algorithms, model cards, and other things

A few other things I’ve been reading and thinking about:

Excel jockeys: In 2017, the New York City Council established the Automated Decision Systems (ADS) Task Force to examine how local government agencies were currently using automated decision systems and to propose guidelines for how they should use such systems in the future. It was the first of its kind in the country, and it generated a lot of excitement. Two years later, the task force’s report has finally been published. It’s pretty thin, and Albert Fox Cahn, who served on the original task force as a representative of CAIR, the Muslim civil rights organization, has a piece in Fast Company that helps explain why. It seems that city officials stonewalled the task force after realizing it wouldn’t just serve as a rubber stamp. One interesting point of contention was the very definition of an automated decision system. Cahn writes:

City officials brought up the specter of unworkable regulations that would apply to every calculator and Excel document, a Kafkaesque nightmare where simply constructing a pivot table would require interagency approval. In lieu of this straw man, they offered a constricted alternative, a world of AI regulation focused on algorithms and advanced machine learning alone.

The problem is that at a moment when the world is fascinated with stories about the dire power of machine learning and other confabulations of big data known with the catchphrase “AI,” some of the most powerful forms of automation still run on Excel, or in simple scripts. You don’t need a multi-million-dollar natural-language model to make a dangerous system that makes decisions without human oversight, and that has the power to change people’s lives. And automated decision systems do that quite a bit in New York City.

This is an important point: the most consequential algorithmic systems are often not particularly advanced. Think about something like shift scheduling software—it’s way less complex than the Facebook News Feed, but it arguably has far greater impact on the lives of millions of low-wage service workers.

To return to the question of automated decision systems, what are some examples of those systems? AI Now has produced a valuable report outlining the different kinds of automated decision systems deployed by various government agencies around the country. AI Now’s Meredith Whittaker, another member of the New York task force, has also been critical of how the city handled the initiative: you can listen to her talk about it on WNYC. Finally, AI Now is hosting an event devoted to automated decision systems in New York on Saturday; if you’re nearby, you should go.

RTFM: A group at Google that includes Margaret Mitchell, Timnit Gebru, Parker Barnes, and others have launched a public “model cards” site for two features of Google’s Cloud Vision API: Face Detection and Object Detection. Initially proposed in a paper earlier this year called “Model Cards for Model Reporting” by Mitchell et al, model cards are intended to give more context on how a machine learning model works, what its limitations and trade-offs are, and how its performance varies across different conditions—the skin tone of a person’s face, for example. In Mitchell’s words, it’s an “example of what transparent documentation in AI could look like.”

There are limits to algorithmic transparency—it can’t take us nearly as far as we need to go, and in certain cases can play a diversionary role—but explaining how machine learning systems work (and making them explainable in the first place) is an integral element of any political project to democratize AI. So I’m excited about Google’s model cards, and I look forward to seeing the experiment develop.

Thermidor: Speaking of Google, the employees who were fired last week as part of the company’s ongoing crackdown on organizers—engineered with the help of IRI Consultants, a union-busting consulting firm—have filed Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charges with the National Labor Relations Board. Google almost certainly violated federal labor law by terminating the employees for engaging in protected concerted activity, not to mention subjecting them to intimidating interrogations where they were asked to provide names of other organizers. That’s no guarantee of a favorable verdict from the NLRB, of course—labor law is easily broken in this country—but they have a strong case.

Stocking stuffers: There’s a new book by Charlton D. McIlwain called Black Software that I really need to read. According to a liveblog of a talk that McIlwain gave at the Strand by J. Nathan Matias, the book “draws an analogy between the development of cocaine and crack cocaine in the 1980s and the history of the tech industry.” I’m interested!

Oily data: Last week, we released a piece from Logic’s new “Nature” issue called “Oil is the New Data.” Written by a Microsoft engineer, it’s a firsthand account of how tech companies are helping the fossil fuel industry use machine learning to intensify extraction. A must-read.